Nuclear Deterrence in the Shadow of Preemption: Revisiting the Incentives of the NPT

The durability of the arms control regime depends on how states interpret the consequences of participation.

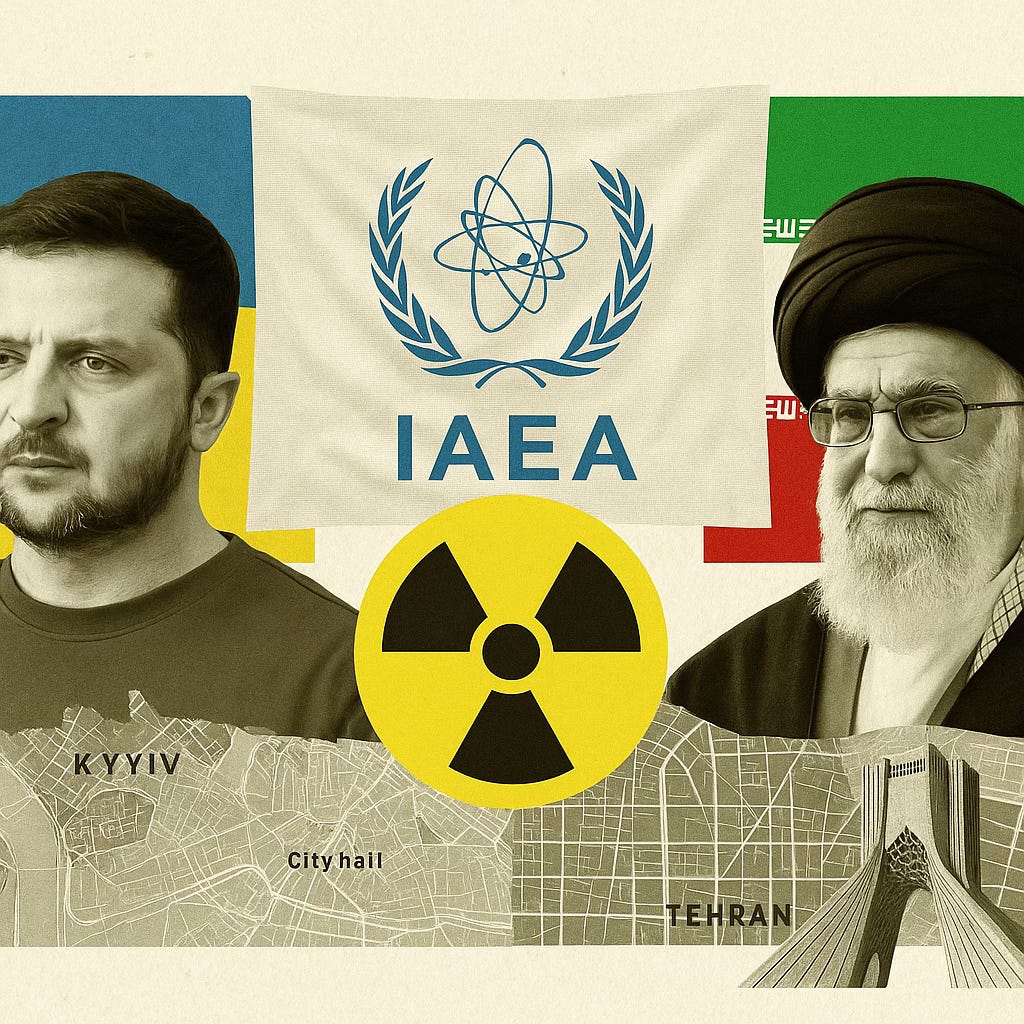

The June Strikes and the Treaty at a Crossroads

In June 2025, a sequence of institutional and military actions reshaped the nuclear landscape. On June 12, 2025, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors passed a resolution declaring Iran in noncompliance with its safeguards obligations, citing Iran's failure to explain uranium traces found at multiple undeclared sites and its obstruction of inspector access. The resolution did not refer Iran to the United Nations Security Council.

The following day, June 13, Israel carried out airstrikes on Iranian nuclear infrastructure. Nine days later, on June 22, the United States launched Operation Midnight Hammer, a coordinated military strike targeting Iranian enrichment and nuclear research facilities.

These actions occurred without UN Security Council authorization, and no imminent threat was publicly cited at the time. Iran remained a signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and subject to IAEA safeguards, albeit with incomplete its compliance. This sequence raises a central question:

If a state can be targeted militarily before institutional enforcement pathways have run their course, what incentives remain to participate in the arms control regime?

The case of Ukraine, often cited as a test of disarmament’s security dividends, offers a further cautionary parallel.

Ukraine's Disarmament and Its Consequences

The calculus for states considering nuclear restraint is increasingly influenced by the case of Ukraine. In 1994, under the Budapest Memorandum, Ukraine surrendered its inherited Soviet nuclear arsenal in exchange for security assurances from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Russia. In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea. In 2022, it launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Ukraine complied with disarmament obligations and relied on international institutions. Yet, its territorial sovereignty was violated. Meanwhile, North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003 and faced limited international pushback, eventually achieving nuclear capability without external invasion. No comparable fate has befallen North Korea, Pakistan, or India, states that developed nuclear weapons outside the NPT regime.

This contrast is not lost on observers. A state that gives up nuclear weapons may suffer external aggression. A state that builds them in secret may avoid it. This perception has direct implications for states evaluating whether nonproliferation offers protection or exposure. The lesson inferred by observers is stark: disarmament may invite risk; deterrence may buy survival.

The Grand Bargain, Fraying

The NPT framework rests on reciprocal obligations: non-nuclear-weapon states agree not to acquire weapons; nuclear-armed states commit to eventual disarmament and to enable access to peaceful nuclear technology.

Iran is a party to the NPT and subject to IAEA inspections. The United States is a recognized nuclear-weapon state under the treaty. Israel, by contrast, is not a signatory and is widely understood to maintain nuclear weapons outside international safeguards.

This structural asymmetry, when paired with the perception of selective enforcement, may erode confidence in the system. If treaty participation does not protect states from coercion or attack, the regime risks becoming a liability rather than a shield.

Key Considerations

Preemptive strikes on safeguarded sites may disincentivize cooperation.

Disarmament without enforcement can leave states exposed.

Strategic opacity may be perceived as more secure than transparency.

The NPT’s deterrent logic is shaped by how participation is treated.

Trust in Transparency, Diminished

Iran's safeguards history includes episodes of concealment and delayed disclosure, including the Natanz and Fordow facilities. The IAEA's June 12, 2025 resolution reflects persistent unanswered questions regarding Lavisan-Shian, Turquzabad, and Varamin.

Nevertheless, Iran remained under safeguards and had not been formally expelled from the verification regime. Yet the military response preceded any UN referral or multilateral enforcement action. This sequence weakens the notion that compliance with verification mechanisms reduces the likelihood of attack.

A regime perceived as responding more sharply to flawed participation than to nonparticipation may inadvertently incentivize strategic opacity.

Precedents Without Process

Strikes on nuclear infrastructure are not unprecedented. The Israeli attacks on Iraq's Osirak reactor in 1981 and on Syria's suspected reactor in 2007 occurred outside the IAEA safeguards structure. In contrast, Iran in 2025 was under active safeguards.

The gap between the June 12 resolution and the June 13 and 22 strikes allowed no time for remediation, negotiation, or escalation through formal channels. While the NPT does not regulate military use of force, its credibility relies on the broader ecosystem of international law, which includes the UN Charter's constraints on unilateral action.

Strategic Logic in Flux

Iran's leadership has previously engaged in nuclear diplomacy, including the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which imposed strict limitations on enrichment in exchange for sanctions relief. The U.S. withdrawal from the agreement in 2018 and subsequent reimposition of sanctions undermined that process.

Recent strikes now target facilities that remain under IAEA surveillance, raising questions about the utility of cooperation. If transparency invites attack while opacity invites caution, the strategic lesson may be reversed.

Some may argue that the international community’s failure to act decisively against North Korea in the early stages of its program contributed to its eventual nuclear breakout. In that view, delayed or absent preemption enabled a trajectory toward irreversible proliferation. From this perspective, the strikes on Iran could be interpreted as an attempt to avoid repeating that outcome. However, such actions also signal to current and future states that the window for diplomacy may close abruptly, and that transparency under safeguards may not guarantee protection from attack. That signal may accelerate the very behaviors the strikes aim to prevent.

When participation appears to expose rather than shield, the logic underpinning the nonproliferation regime begins to fracture. For future threshold states, the choice may no longer be framed by legality, but by survival.

The Fallout for the NPT

The NPT remains in force. But its future depends on whether its incentives align with the security calculations of its members.

A safeguarded state struck before institutional recourse is exhausted may conclude that participation increases exposure rather than protection. Others may draw the same conclusion. For threshold states weighing their options today, the perceived lessons from Iran, Ukraine, and North Korea may recalibrate the logic of restraint.

The greatest risk may lie not in any single case, but in the potential normalization of preemption without process. That precedent, once set, may shape the decisions of current and future threshold states for decades to come. When participation appears to expose rather than shield, the logic underpinning the nonproliferation regime begins to fracture. For future threshold states, the choice may no longer be framed by legality, but by survival.

This article does not take a position on the legality or necessity of any specific action. It examines the structural signals conveyed by recent events through the lens of arms control theory and regime design.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not represent the official position of any affiliated institution. This article reflects information available as of June 28, 2025, and events may continue to evolve.